Translator’s note: mr. is the traditional title for university graduates in law. The abbreviated Dutch title is written before the name.

Rb. Den Haag, 24-06-2015, nr. C/09/456689 / HA ZA 13-1396 (English translation)

ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2015:7196

- Instantie

Rechtbank Den Haag

- Datum

24-06-2015

- Zaaknummer

C/09/456689 / HA ZA 13-1396 (English translation)

- Vakgebied(en)

Civiel recht algemeen (V)

- Brondocumenten en formele relaties

ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2015:7196, Uitspraak, Rechtbank Den Haag, 24‑06‑2015

Hoger beroep: ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2018:2610, Bekrachtiging/bevestiging

Uitspraak 24‑06‑2015

Inhoudsindicatie

The Hague District Court has ruled today that the State must take more action to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions in the Netherlands. The State also has to ensure that the Dutch emissions in the year 2020 will be at least 25% lower than those in 1990. The Urgenda Foundation had requested the court for a ruling. Current policy below the norm The parties agree that the severity and scope of the climate problem make it necessary to take measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Based on the State’s current policy, the Netherlands will achieve a reduction of 17% at most in 2020, which is below the norm of 25% to 40% for developed countries deemed necessary in climate science and international climate policy. State must provide protection The State must do more to avert the imminent danger caused by climate change, also in view of its duty of care to protect and improve the living environment. The State is responsible for effectively controlling the Dutch emission levels. Moreover, the costs of the measures ordered by the court are not unacceptably high. Therefore, the State should not hide behind the argument that the solution to the global climate problem does not depend solely on Dutch efforts. Any reduction of emissions contributes to the prevention of dangerous climate change and as a developed country the Netherlands should take the lead in this. With this order, the court has not entered the domain of politics. The court must provide legal protection, also in cases against the government, while respecting the government’s scope for policymaking. For these reasons, the court should exercise restraint and has limited therefore the reduction order to 25%, the lower limit of the 25%-40% norm. Urgenda The legal proceedings were instituted by the Urgenda Foundation, a citizens’ platform which develops plans and measures to prevent climate change. The foundation also represents 886 individuals in this case.

Partij(en)

judgment

THE HAGUE DISTRICT COURT

Chamber for Commercial Affairs

case number / cause list number: C/09/456689 / HA ZA 13-1396

Judgment of 24 June 2015

in the case of

the foundation

URGENDA FOUNDATION, acting on its own behalf as well as in its capacity as representative ad litem and representative of the individuals included in the list attached to the summons,

with its registered office and principal place of business in Amsterdam,

claimant,

lawyers mr.1.R.H.J. Cox of Maastricht and mr. J.M. van den Berg of Amsterdam,

versus

the legal person under public law

THE STATE OF THE NETHERLANDS (MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT),

seated in The Hague,

defendant,

lawyers mr. G.J.H. Houtzagers of The Hague and mr. E.H.P. Brans of The Hague.

Parties are hereinafter referred to as Urgenda and the State.

(Translation) Only the Dutch text of the ruling is authoritative.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 THE PROCEEDINGS 1

2 THE FACTS 2

A. The Parties 2.1

B. Reasons for these proceedings 2.6

C. Scientific organisations and publications 2.8

IPCC 2.8

AR4/2007 2.12

AR5/2013 2.18

PBL and KNMI 2.22

EDGAR 2.25

UNEP 2.29

D. Climate change and the development of legal and policy frameworks 2.34

In a UN context 2.35

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change 1992 2.35

Kyoto Protocol 1997 and Doha Amendment 2012 2.42

Climate change conferences (Conference of the Parties - COP) 2.47

a) Bali Action Plan 2007 2.48

b) The Cancun Agreements 2010 2.49

c) Durban 2011 2.51

In a European context 2.53

In a national context 2.69

3 THE DISPUTE 3

4 THE ASSESSMENT 4

A. Introduction 4.1

B. Urgenda’s standing (acting on its own behalf) 4.4

C. Current climate science and climate policy 4.11

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the IPCC 4.11

The IPCC reports 4.13

The maximum level of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere 4.20

The reduction targets 4.23

The effect of the reduction measures thus far 4.30

Conclusions and specification of the scope of the dispute 4.31

D. Legal obligation of the State? 4.35

Introduction 4.35

Contravention of a legal obligation 4.36

Article 21 of the Constitution and international conventions 4.36

Violation of a personal right 4.45

Articles 2 and 8 ECHR 4.45

Book 5, Section 37 of the Dutch Civil Code 4.51

Intermediate conclusion about the duty of care 4.52

Breach of standard of due care observed in society, discretionary power 4.53

Factors to determine duty of care 4.54

Duty of care 4.64

(i-iii) the nature and extent of the damage ensuing from climate change, the knowledge and foreseeability of this damage and the chance that hazardous climate change will occur 4.64

(iv) the nature of the acts (or omissions) of the State 4.66

(v) the onerousness of taking precautionary measures 4.67

(vi) the discretion of the State to execute its public duties – with due regard for the public-law principles 4.74

Conclusion about the duty of care and determining the reduction target 4.83

Attributability 4.87

Damages 4.88

Causal link 4.90

Relativity 4.91

Conclusion regarding the State’s legal obligation 4.93

E. The system of separation of powers 4.94

F. Consequences of the foregoing for components of the claim 4.103

The reduction order 4.103

Declaratory decisions 4.104

The information order 4.106

G. Urgenda’s standing (acting on behalf of the principles) 4.108

H. Costs of the proceedings 4.110

5 THE RULING 5

1. THE PROCEEDINGS

1.1.

The course of the proceedings is evidenced by:

- the summons, with Exhibits 1-51,

- the defence, with Exhibits 1-15,

- the reply and also change of claim, with Exhibits 52-98,

- the rejoinder, with Exhibits 16-29,

- the document containing Exhibits 99-103 on the part of Urgenda,

- the report of the hearing of 14 April 2015, with the documents stated therein,

- the letters of 30 April and 11 May 2015 of mr. Brans and of 6 and 12 May 2015 of mr. Cox, with comments on the report,

- the letter of 13 May 2015 of the court registry to the Parties.

1.2.

The court will read the report of the hearing of 14 April 2015 with due observance of the comment of the State in its letter of 30 April 2015 and of the comments of Urgenda in its letter of 6 May 2015 regarding an attribution. In Urgenda’s other comments the court sees insufficient reason to amend the report, also in light of the State’s response to the comments. However, it should be noted that the report is only an abridged version of that which was discussed at the hearing or of the conclusions drawn by the court from that which was discussed at the hearing.

1.3.

Finally, judgment was scheduled for today.

2. THE FACTS

A. Parties

2.1.

Urgenda (a contraction of “urgent agenda”) arose from the Dutch Research Institute for Transitions (Drift) at Erasmus University Rotterdam, an institute for the transition to a sustainable society. Urgenda is a citizens’ platform with members from various domains in society, such as the business community, media communication, knowledge institutes, government and non-governmental organisations. The platform is involved in the development of plans and measures to prevent climate change.

2.2.

Urgenda was established by a notarial deed of 17 January 2008. Article 2 of the by-laws (“purpose and principle”) reads as follows:

“1. The purpose of the Foundation is to stimulate and accelerate the transition processes to a more sustainable society, beginning in the Netherlands.

2. The Foundations aims to meet this objective by, among other things:

a. establishing a sustainability platform which will develop a vision for a sustainable Netherlands in the year two thousand and fifty (2050), as a motivating perspective for all parties involved in sustainability;

b. identifying organisations and initiatives which are involved in sustainability and connecting them to form a sustainability movement;

c. drawing up an action plan for the next fifty (50) years and implementing it with partners from society;

d. initiating, stimulating and assisting Icon projects and regional sustainability projects which subscribe to Urgenda’s objectives and which serve as a means of communication in order to show third parties what sustainability means in actual practice.”

2.3.

Regarding the meaning of the term “sustainability”, in its by-laws Urgenda refers to the definition of sustainable development in the 1987 report of the World Commission on Environment and Development of the United Nations (UN), also known as the Brundtland Report, which reads as follows:

“Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

2.4.

In these proceedings, Urgenda also acts on behalf of 886 individuals who have authorised Urgenda to also conduct these proceedings on their behalf.

2.5.

The Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, as a part of the State, is responsible (among other things) for ensuring a healthy and safe living environment, managing scarce resources and environmental compartments, and promoting the development of the Netherlands as a safe, liveable, accessible and competitive delta.

B. Reasons for these proceedings

2.6.

In its letter to the Prime Minister dated 12 November 2012, Urgenda requested the State to commit and undertake to reduce CO2 emissions in the Netherlands by 40% by 2020, as compared to the emissions in 1990.

2.7.

In her letter dated 11 December 2012, the State Secretary for Infrastructure and the Environment replied to Urgenda’s letter as follows (among other things):

“I share your concerns over the absence of sufficient international action as well as your concerns that both the scale of the problem and the urgency of a successful approach in the public debate are insufficiently tangible (…).

The most important thing is to eventually have a stable and widely supported policy framework which will lead to sufficient action to keep the long-term perspective of a 80%-95% CO2 reduction by 2050 within reach (…)

It is also clear that collective, global actions are required to keep climate change within acceptable limits. In this context of collective actions, the 25%-40% reduction you refer to in your letter was always the objective. The EU’s offer to pursue a 30% reduction by 2020, on the condition that other countries pursue similar reductions, falls within that range. It is a major problem that the current collective, global efforts are falling short and fail to monitor the limitation of the average global temperature rise to 2 degrees. I will cooperate with national and international partners to launch and support initiatives to tackle this (…).

C. Scientific organisations and publications

IPCC

2.8.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is a scientific body established by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988, under the auspices of the UN. The IPCC aims to acquire insight into all aspects of climate change, such as the risks, consequences and options for adaptation and mitigation. Mitigation (reducing the problem) is intended to prevent or limit further climate change. Adaptation (adapting to the consequences) is aimed at attempting to make nature, society and the economy less vulnerable to a changing climate. The IPCC itself does not conduct research nor does it keep climate-related data, but studies and assesses the latest scientific, technical and socio-economic information produced worldwide and publishes reports about it.

2.9.

The IPCC is not just a scientific body, but also an intergovernmental organisation. Membership is open to all states which are members of the UN and the WMO. The IPCC currently has 195 countries as members, including the Netherlands.

2.10.

Upon its establishment, the IPCC was divided into three working groups, which are responsible for identifying and listing the following subjects:

Working group I: existing scientific knowledge about the climate system and climate change;

Working group II: the consequences of climate change for the environment, economy and society;

Working group III: the possible strategies in response to these changes.

2.11.

Since its inception, the IPCC has published five reports (each consisting of four subreports). The most recent reports are relevant for these proceedings: the “Fourth Assessment Report” from 2007 (hereinafter: AR4/2007) and the “Fifth Assessment Report” from 2013/2014 (hereinafter: AR5/2013).

AR4/2007

2.12.

In this report, the IPCC – in so far as currently still relevant – established that a global temperature rise of 2°C above the pre-industrial level (up to the year 1850) creates the risk of dangerous, irreversible change of climate:2.

“Confidence has increased that a 1 to 2 oC increase in global mean temperature above 1990 levels (about 1.5 to 2.5o C above pre-industrial) poses significant risks to many unique and threatened systems including many biodiversity hotspots.”

2.13.

In this report, the IPCC provided insight into options for not exceeding the 2°C limit based on the table below.3.To this end, the IPCC provided an overview of the link between the various emission scenarios, stabilisation targets and temperature change, while taking account of a climate sensitivity of probably ( >66%) 2-4.5°C. “Climate sensitivity” represents the extent to which temperature is expected to respond to a doubling of the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. The report proceeds to make calculations with a “best estimate” climate sensitivity of 3°C.

“Table 3.10: Properties of emissions pathways for alternative ranges of C02 and C02-eq stabilization targets. Post-TAR stabilization scenarios in the scenario database (see also Sections 3.2 and 3.3); data source: after Nakicenovic et al., 2006 and Hanaoka et al., 2006)

Class | Anthropogenic addition to radiative forcing at stabilization (Wim2) | Multi-gas concentration level (ppmv C02-eq) | Stabilization level for C02 only, consistent with multi-gas level (ppmv C02) | Number of scenario studies | Global mean temperature C increase above pre-industrial at equilibrium, using best estimate of climate sensitivity c) | Likely range of global mean temperature C increase above pre- industrial at equilibrium a) | Peaking year for C02 emissions b) | Change in global emissions in 2050 (% of 2000 Class emissions) b) |

I II III IVV VI | 2.5-3.0 3.0-3.5 3.5-4.0 4.0-5.0 5.0-6.0 6.0-7.5 | 445-490 490-535 535-590 590-710 710-855 855-1130 | 350-400 400-440 440-485 485-570 570-660 660-790 | 6 18 21 118 9 5 | 2.0-2.4 2.4-2.8 2.8-3.2 3.2-4.0 4.0-4.9 4.9-6.1 | 1.4-3.6 1.6-4.2 1.9-4.9 2.2-6.1 2.7-7.3 3.2-8.5 | 2000-2015 2000-2020 2010-2030 2020-2060 2050-2080 2060-2090 | -85 to -50 -60 to -30 -30 to +5 +10 to +60 +25 to +85 +90 to +140 |

Notes:

a. Warming for each stabilization class is calculated based on the variation of climate sensitivity between 2°C —4.5°C, which corresponds to the likely range of climate sensitivity as defined by Meehl et al. (2007,Chapter 10).

b. Ranges correspond to the 70% percentile of the post-TAR scenario distribution.

c. ‘Best estimate’ refers to the most likely value of climate sensitivity, i.e. the mode (sea Meehl et al. (2007, Chapter 10) and Table 3.9”

2.14.

This table (after I) shows that in order to limit the temperature rise to 2-2.4°C, the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will have to be stabilised at a level of 445-490 ppmv (parts per million by volume) CO2-eq (CO2 and other anthropogenic greenhouse gases. This unit, which hereinafter is referred to with the abbreviation “ppm”, designates the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The report states that, assuming a climate sensitivity of 3°C, a temperature rise of 2°C maximum can only be achieved when the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is stabilised at about 450 ppm:4.

“This ‘best estimate’ assumption shows that the most stringent (category I) scenarios could limit global mean temperature increases to 2°C–2.4°C above pre-industrial levels, at equilibrium, requiring emissions to peak within 10 years. Similarly, limiting temperature increases to 2°C above preindustrial levels can only be reached at the lowest end of the concentration interval found in the scenarios of category I (i.e. about 450 ppmv CO2-eq using ‘best estimate’ assumptions). By comparison, using the same ‘best estimate’ assumptions, category II scenarios could limit the increase to 2.8°C–3.2°C above pre-industrial levels at equilibrium, requiring emissions to peak within the next 25 years, whilst category IV scenarios could limit the increase to 3.2°C–4°C above pre-industrial at equilibrium requiring emissions to peak within the next 55 years. Note that Table 3.10 category IV scenarios could result in temperature increases as high as 6.1°C above pre-industrial levels, when the likely range for the value of climate sensitivity is taken into account.”

2.15.

Following an analysis of the various scenarios about the question which emission reductions are needed to achieve certain particular climate goals, the IPCC concluded that in order to reach a maximum of 450 ppm, the total emission of greenhouse gases by the Annex I countries (including the Netherlands, as explained below) must be lower than in 1990. In this scenario, the total emission of these countries will have to have been reduced by 80 to 95% compared to 1990. See the table below.5.

“Box 13.7 The range of the difference between emissions in 1990 and emission allowances in 2020/2050 for various GHG [Greenhouse Gasses; added by the court] concentration levels for Annex I and non-Annex I countries as a groupa

Scenario category | Region | 2020 | 2050 |

A-450 ppm CO2-eqb | Annex I | –25% to –40% | –80% to –95% |

Non-Annex I | Substantial deviation from baseline in Latin America, Middle East, East Asia and Centrally-Planned Asia | Substantial deviation from baseline in all regions | |

B-550 ppm CO2-eq | Annex I | -10% to -30% | -40% to -90% |

Non-Annex I | Deviation from baseline in Latin America and Middle East, East Asia | Deviation from baseline in most regions, especially in Latin America and Middle East | |

C-650 ppm CO2-eq | Annex I | 0% to -25% | -30% to -80% |

Non-Annex I | Baseline | Deviation from baseline in Latin America and Middle East, East Asia |

Notes:

a The aggregate range is based on multiple approaches to apportion emissions between regions (contraction and convergence, multistage, Triptych and intensity targets, among others). Each approach makes different assumptions about the pathway, specific national efforts and other variables. Additional extreme cases – in which Annex I undertakes all reductions, or non-Annex I undertakes all reductions – are not included. The ranges presented here do not imply political feasibility, nor do the results reflect cost variances.

b Only the studies aiming at stabilization at 450 ppm CO2-eq assume a (temporary) overshoot of about 50 ppm (See Den Elzen and Meinshausen, 2006). (…)”

2.16.

A table comparable to the one in 2.13 has been included in the Technical Summary of the contribution of Working Group III to AR4/2007 (p. 39), in which the following is stated (p. 90):

“Under most equity interpretations, developed countries as a group would need to reduce their emissions significantly by 2020 (10–40% below 1990 levels) and to still lower levels by 2050 (40–95% below 1990 levels) for low to medium stabilization levels (450–550ppm CO2-eq) (see also Chapter 3).”

The Bali Action Plan, which is discussed below, refers to these sections and to the table in 2.15.

2.17.

The IPCC report also states that mitigation is generally better than adaptation:6.

“Over the next 20 years or so, even the most aggressive climate policy can do little to avoid warming already ‘loaded’ into the climate system. The benefits of avoided climate change will only accrue beyond that time. Over longer time frames, beyond the next few decades, mitigation investments have a greater potential to avoid climate change damage and this potential is larger than the adaptation options that can currently be envisaged (medium agreement, medium evidence).”

AR5/2013

2.18.

In 2013-2014, the IPCC published its latest insights into the scope, effects and causes of climate change. In the report concerned (AR5/2013) the IPCC, in accordance with AR4/2007, established that the earth has been warming as a result of the high increase of CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution (base year 1850) and that this has been caused by human activity, particularly the combustion of oil, natural gas and coal as well as deforestation:7.

“Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950’s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millenia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen, and the concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased (…)

Each of the last three decades has been successively warmer at the Earth’s surface than any preceding decade since 1850 (…). In the Northern Hemisphere, 1983-2012 was likely the warmest 30-year period of the last 1400 years (medium confidence).

The globally averaged combined land and ocean surface temperature data as calculated by a linear trend, show a warming of 0.85 [0.65 to 1.06]°C, over the period 1880 to 2012, when multiple independently produced datasets exist. The total increase between the average of the 1850-1900 period and the 2003-2012 period is 0.78 [0.72 to 0.85]°C, based on the single longest dataset available (…).

Human influence has been detected in warming of the atmosphere and the ocean, in changes in the global water cycle, in reductions in snow and ice, in global mean sea level rise, and in changes in some climate extremes (…). This evidence for human influence has grown since AR4. It is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.”

2.19.

In the report, the IPCC also concluded that if concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will have stabilised to about 450 ppm in 2100, there is a 66% chance that the rise of the global temperature will not exceed 2°C. In order to achieve a concentration level of 450 ppm in 2100, the global greenhouse emissions in 2050 will have to be 40 to 70% lower than those in the year 2010. The total of emissions will have to have been reduced to zero or even to below zero (as compared to the comparative year) by 2100:8.

“Mitigation scenarios in which it is likely that the temperature change caused by anthropogenic GHG emissions can be kept to less than 2 °C relative to pre-industrial levels are characterized by atmospheric concentrations in 2100 of about 450 ppm CO2eq (high confidence). Mitigation scenarios reaching concentration levels of about 500 ppm CO2eq by 2100 are more likely than not to limit temperature change to less than 2 °C relative to pre-industrial levels, unless they temporarily ‘overshoot’ concentration levels of roughly 530 ppm CO2eq before 2100, in which case they are about as likely as not to achieve that goal. Scenarios that reach 530 to 650 ppm CO2eq concentrations by 2100 are more unlikely than likely to keep temperature change below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels. Scenarios that exceed about 650 ppm CO2eq by 2100 are unlikely to limit temperature change to below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels. Mitigation scenarios in which temperature increase is more likely than not to be less than 1.5°C relative to pre-industrial levels by 2100 are characterized by concentrations in 2100 of below 430 ppm CO2eq. Temperature peaks during the century and then declines in these scenarios. (…)

Scenarios reaching atmospheric concentration levels of about 450 ppm CO2eq by 2100 (consistent with a likely chance to keep temperature change below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels) include substantial cuts in anthropogenic GHG emissions by mid-century through large-scale changes in energy systems and potentially land use (high confidence). Scenarios reaching these concentrations by 2100 are characterized by lower global GHG emissions in 2050 than in 2010, 40% to 70% lower globally, and emissions levels near zero GtCO2eq or below in 2100. In scenarios reaching 500 ppm CO2eq by 2100, 2050 emissions levels are 25% to 55% lower than in 2010 globally. In scenarios reaching 550 ppm CO2eq, emissions in 2050 are from 5% above 2010 levels to 45% below 2010 levels globally (…). At the global level, scenarios reaching 450 ppm CO2eq are also characterized by more rapid improvements of energy efficiency, a tripling to nearly a quadrupling of the share of zero- and low-carbon energy supply from renewables, nuclear energy and fossil energy with carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS), or bioenergy with CCS (BECCS) by the year 2050 (…). These scenarios describe a wide range of changes in land use, reflecting different assumptions about the scale of bioenergy production, afforestation, and reduced deforestation. All of these emissions, energy, and land-use changes vary across regions. Scenarios reaching higher concentrations include similar changes, but on a slower timescale. On the other hand, scenarios reaching lower concentrations require these changes on a faster timescale. […]

Mitigation scenarios reaching about 450 ppm CO2eq in 2100 typically involve temporary overshoot of atmospheric concentrations, as do many scenarios reaching about 500 ppm to 550 ppm CO2eq in 2100. Depending on the level of the overshoot, overshoot scenarios typically rely on the availability and widespread deployment of BECCS and afforestation in the second half of the century. The availability and scale of these and other Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies and methods are uncertain and CDR technologies and methods are, to varying degrees, associated with challenges and risks (high confidence) (…). CDR is also prevalent in many scenarios without overshoot to compensate for residual emissions from sectors where mitigation is more expensive. There is only limited evidence on the potential for large-scale deployment of BECCS, large-scale afforestation, and other CDR technologies and methods.

Estimated global GHG emissions levels in 2020 based on the Cancún Pledges are not consistent with cost effective long-term mitigation trajectories that are at least as likely as not to limit temperature change to 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels (2100 concentrations of about 450 and about 500 ppm CO2eq), but they do not preclude the option to meet that goal (high confidence). Meeting this goal would require further substantial reductions beyond 2020. The Cancún Pledges are broadly consistent with cost-effective scenarios that are likely to keep temperature change below 3°C relative to preindustrial levels. […]

Delaying mitigation efforts beyond those in place today through 2030 is estimated to substantially increase the difficulty of the transition to low longer-term emissions levels and narrow the range of options consistent with maintaining temperature change below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels (high confidence). Cost-effective mitigation scenarios that make it at least as likely as not that temperature change will remain below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels (2100 concentrations between about 450 and 500 ppm CO2eq) are typically characterized by annual GHG emissions in 2030 of roughly between 30 GtCO2eq and 50 GtCO2eq (Figure SPM.5, left panel). Scenarios

with annual GHG emissions above 55 GtCO2eq in 2030 are characterized by substantially higher rates of emissions reductions from 2030 to 2050 (…); much more rapid scale-up of low-carbon energy over this period (…); a larger reliance on CDR technologies in the long-term (…); and higher transitional and long-term economic impacts (…). Due to these increased mitigation challenges, many models with annual 2030 GHG emissions higher than 55 GtCO2eq could not produce scenarios reaching atmospheric concentration levels that make it as likely as not that temperature change will remain below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels.”

2.20.

The following has been observed about the scope of the emissions:9.

“Total anthropogenic GHG emissions have continued to increase over 1970 to 2010 with larger absolute decadal increases toward the end of this period (high confidence). Despite a growing number of climate change mitigation policies, annual GHG emissions grew on average by 1.0 gigatonne carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2eq) (2.2%) per year from 2000 to 2010 compared to 0.4 GtCO2eq (1.3%) per year from 1970 to 2000 (…). Total anthropogenic GHG emissions were the highest in human history from 2000 to 2010 and reached 49 (±4.5) GtCO2eq/yr in 2010. The global economic crisis 2007/2008 only temporarily reduced emissions.”

2.21.

The IPCC expects that temperatures on earth will have increased by 3.7 to 4.8°C by 2100 and that the 450 ppm level will have been exceeded in 2030 if reduction measures fail to materialise:10.

“Without additional efforts to reduce GHG emissions beyond those in place today, emissions growth is expected to persist driven by growth in global population and economic activities. Baseline scenarios, those without additional mitigation, result in global mean surface temperature increases in 2100 from 3.7°C to 4.8°C compared to pre-industrial levels10 (median values; the range is 2.5°C to 7.8°C when including climate uncertainty (…) (high confidence). The emission scenarios collected for this assessment represent full radiative forcing including GHGs, tropospheric ozone, aerosols and albedo change. Baseline scenarios (scenarios without explicit additional

efforts to constrain emissions) exceed 450 parts per million (ppm) CO2eq by 2030 and reach CO2eq concentration levels between 750 and more than 1300 ppm CO2eq by 2100. This is similar to the range in atmospheric concentration levels between the RCP 6.0 and RCP 8.5 pathways in 2100. For comparison, the CO2eq concentration in 2011 is estimated to be 430 ppm (uncertainty range 340 – 520 ppm).”

PBL and KNMI

2.22.

The Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) is a national independent research institute working in the field of the environment, nature and spatial planning. It conducts research, both when asked and on its own initiative, in support of political and administrative policies. Established in 2008, the institute currently forms part of the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment.

2.23.

The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) is the Dutch national institute for meteorology and seismology established by law. The institute provides the best information available in the field of weather, climate and earthquakes in support of the security, accessibility, liveability and prosperity of the Netherlands. The KNMI represents the Netherlands in the IPCC and other bodies.

2.24.

Both the PBL and the KNMI analyse results of the IPCC reports and report about the consequences of the IPCC findings for the Netherlands.

EDGAR

2.25.

The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) is a database in which a country’s emission data are collected based on which the global emission of greenhouse gases can be determined. EDGAR is a joint project of the European Commission and the PBL.

2.26.

According to the latest data from EDGAR the following amounts of greenhouse gases have been emitted worldwide and in the Netherlands:

Worldwide

1990 38232170.06 megatons (hereinafter: Mt) CO2-eq.

2010 50911113.68 Mt CO2-eq

2012 53526302.83 Mt CO2-eq

The Netherlands

1990 224468.09 Mt CO2-eq

2010 212418.45 Mt CO2-eq

2012 19587376 Mt CO2-eq

2.27.

In 2010, the Dutch share in the global emissions was 0.42%; the Chinese share in that year was 21.97%; the share of the United States was 13.19%; the total share of the European Union (then 27 countries) was 9.5%; the Brazilian share was 5.7%; India’s share was 5.44% and Russia’s share was 5.11%.

2.28.

Per capita emissions in the Netherlands in 2010 were 12.78 tons CO2-eq. and in 2012 11.72 tons CO2-eq. In China, per capita emissions in 2012 were 9.04 tons CO2-eq.; in the United States 19.98 tons CO2-eq.; in Brazil 15.05 tons CO2-eq.; in India 2.43 tons CO2-eq. and in Russia 19.58 tons CO2-eq.

UNEP

2.29.

The UNEP, referred to in 2.8, has issued annual reports about the “emissions gap” since 2010. The gap is the difference between the desired emissions level in a certain year and the level of emissions anticipated for that year based on the reduction goals pledged by the countries concerned.

2.30.

The “executive summary” of the Emissions Gap Report 2013 includes the following:

“(...) This report confirms and strengthens the conclusions of the three previous analyses that current pledges and commitments fall short of that goal. It further says that, as emissions of greenhouse gases continue to rise rather than decline, it becomes less and less likely that emissions will be low enough by 2020 to be on a least-cost pathway towards meeting the 2°C target.

As a result, after 2020, the world will have to rely on more difficult, costlier and riskier means of meeting the target – the further from the least-cost level in 2020, the higher these costs and the greater the risks will be.

(…)

2. What emission levels are anticipated for 2020?

Global greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 are estimated at 59 GtCO2e per year under a business-as-usual scenario. If implemented fully, pledges and commitments would reduce this by 3–7 GtCO2e per year (…).

3. What is the latest estimate of the emissions gap in 2020?

(…) Least-cost emission pathways consistent with a likely chance of keeping global mean temperature increases below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels have a median level of 44 GtCO2e in 2020 (range: 38–47 GtCO2e). Assuming full implementation of the pledges, the emissions gap thus amounts to between 8–12 GtCO2e per year in 2020 (…).

6. What are the implications of later action scenarios that still meet the 1.5°C and 2°C targets?

Based on a much larger number of studies than in 2012, this update concludes that so-called later-action scenarios have several implications compared to least cost scenario’s, including: (i) much higher rates of global emission reductions in the medium term; (ii) greater lock-in of carbon-intensive infrastructure; (iii) greater dependence of certain technologies in the medium-term; (iv) greater costs of mitigation in the medium- and long term, and greater risks of economic disruption; and (v) greater risks of failing to meet the 2°C target. For these reasons later-action scenarios may not be feasible in practise and, as a result, temperature targets could be missed.

(…) although later-action scenarios might reach the same temperature targets as their least-cost counterparts, later-action scenarios pose greater risks of climate impacts for four reasons. First delaying action allows more greenhouse gases to build-up in the atmosphere in the near term, thereby increasing the risk that later emission reductions will be unable to compensate for this build up. Second, the risk of overshooting climate targets for both atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases and global temperature increase is higher with later-action scenarios. Third, the near-term rate of temperature is higher, which implies greater near-term climate impacts. Lastly, when action is delayed, options to achieve stringent levels of climate protection are increasingly lost.”

2.31.

Chapter 2 of the report contains the following section:

“2.4.5 Pledged reduction effort by Annex I and non-Annex I countries

For Annex I parties, total emissions as a group of countries for the four pledge cases are estimated to be 3–16 percent below 1990 levels in 2020. For non-Annex I parties, total emissions are estimated to be 7–9 percent lower than business-as-usual emissions. This implies that the aggregate Annex I countries’ emission goals fall short of reaching the 25–40 percent reduction by 2020, compared with 1990, suggested in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (…).”

2.32.

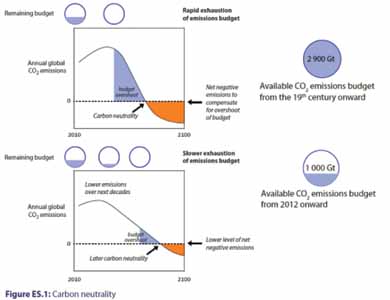

In contrast to previous reports, the Emissions Gap Report 2014 mainly focuses on the “carbon dioxide emissions budget”. The UNEP concludes that in order to be able to maintain the target of a maximum global temperature rise of 2°C above the pre-industrial level (hereinafter: the 2°C target), the CO2 budget may not exceed 3,670 gigatonne (hereinafter: Gt). According to the UNEP, at the beginning of the nineteenth century this budget totaled about 2,900 Gt CO2, of which about 1,000 Gt remains. In the report, the UNEP investigated – in short –the best way to spend this budget (and thereby: which reductions are required). Attention was also paid to the question, given the 2°C target, at what point the world needs to be CO2-neutral (a net result of anthropogenic positive and negative CO2 emissions of zero). The UNEP has depicted this in the following figure:

2.33.

The “executive summary” of the 2014 report furthermore states the following:

“6. What about the emissions gap in 2030?

(…)

This report estimates that global emissions in 2030 consistent with having a likely chance of staying

within the 2 °C target are about 42 Gt CO2e.

As for expected emissions in 2030, the range of the pledge cases in 2020 (52–54 Gt CO2e) was extrapolated to give median estimates of 56–59 Gt CO2e in 2030.

The emissions gap in 2030 is therefore estimated to be 14–17 Gt CO2e (56 minus 42 and 59 minus 42). This is equivalent to about a third of current global greenhouse emissions (or 26–32 per cent of 2012 emission levels).

As a reference point, the gap in 2030 relative to business-as-usual emissions in that year (68 Gt CO2e) is 26 Gt CO2e. The good news is that the potential to reduce global emissions relative to the baseline is estimated to be 29 Gt CO2e, that is, larger than this gap. This means that it is feasible to close the 2030 gap and stay within the 2°C limit.”

D. Climate change and the development of legal and policy frameworks

2.34.

In light of climate change, agreements have been made and instruments have been developed in an international and European context in order to counter the problems of climate change, which have impacted the national legal and policy frameworks.

In a UN context

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change 1992

2.35.

In 1992, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (hereinafter: the UN Climate Change Convention) was agreed and signed under the responsibility of the UN. The UN Climate Change Convention entered into effect on 21 March 1994. Currently, 195 Member States have ratified the convention, including the Netherlands and (the predecessor of) the European Union (both in 1993).

2.36.

The purpose of the Convention, in brief, is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and thereby prevent the undesired consequences of climate change. Among other things, Its opening words state the following:

“Acknowledging that the global nature of climate change calls for the widest possible cooperation by all countries and their participation in an effective and appropriate international response, in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities and their social and economic conditions,

Recalling also that States have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law, the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental and developmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction,

Reaffirming the principle of sovereignty of States in international cooperation to address climate change,

Determined to protect the climate system for present and future generations, (…)”

2.37.

Article 2 of the UN Climate Change Convention describes the objective as follows:

The ultimate objective of this Convention and any related legal instruments that the Conference of the Parties may adopt is to achieve, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention, stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.

2.38.

Article 3 of the UN Climate Change Convention contains the following principles, among other things:

1. The Parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof.

(…)

3. The Parties should take precautionary measures to anticipate, prevent or minimize the causes of climate change and mitigate its adverse effects. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing such measures, taking into account that policies and measures to deal with climate change should be cost-effective so as to ensure global benefits at the lowest possible cost. To achieve this, such policies and measures should take into account different socio-economic contexts, be comprehensive, cover all relevant sources, sinks and reservoirs of greenhouse gases and adaptation, and comprise all economic sectors. Efforts to address climate change may be carried out cooperatively by interested Parties.

4. The Parties have a right to, and should, promote sustainable development. Policies and measures to protect the climate system against human-induced change should be appropriate for the specific conditions of each Party and should be integrated with national development programmes, taking into account that economic development is essential for adopting measures to address climate change.

2.39.

The signatories to the UN Climate Change Convention constitute two groups of countries: (1) the developed countries, as listed in Annex I to the Convention, also referred to as “Annex I countries”, and (2) the developing countries, or “non-Annex I countries”, being all other countries which have ratified the UN Climate Change Convention. The Netherlands is an Annex I country. Article 4, paragraph 2 of the UN Climate Change Convention stipulates the following in particular regarding the Annex I countries:

The developed country Parties and other Parties included in Annex I commit themselves specifically as provided for in the following:

( a) Each of these Parties shall adopt national policies and take corresponding measures on the mitigation of climate change, by limiting its anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases and protecting and enhancing its greenhouse gas sinks and reservoirs. These policies and measures will demonstrate that developed countries are taking the lead in modifying longer-term trends in anthropogenic emissions consistent with the objective of the Convention, recognizing that the return by the end of the present decade to earlier levels of anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol would contribute to such modification, and taking into account the differences in these Parties' starting points and approaches, economic structures and resource bases, the need to maintain strong and sustainable economic growth, available technologies and other individual circumstances, as well as the need for equitable and appropriate contributions by each of these Parties to the global effort regarding that objective. These Parties may implement such policies and measures jointly with other Parties and may assist other Parties in contributing to the achievement of the objective of the Convention and, in particular, that of this subparagraph;

( b) In order to promote progress to this end, each of these Parties shall communicate, within six months of the entry into force of the Convention for it and periodically thereafter, and in accordance with Article 12, detailed information on its policies and measures referred to in subparagraph (a) above, as well as on its resulting projected anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol for the period referred to in subparagraph (a), with the aim of returning individually or jointly to their 1990 levels these anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol. This information will be reviewed by the Conference of the Parties, at its first session and periodically thereafter, in accordance with Article 7; (…)

2.40.

The article thus means that the Annex I countries, separately or jointly, have assumed the obligation to have reduced the growth of their greenhouse gas emissions to the level of 1990 by the year 2000. All Member States are furthermore obliged to annually report their emissions to the UN Climate Change Convention secretariat. The obligations of all other Parties to the Convention (the “non-Annex I countries”) are less far-reaching and they do not have to introduce emission reductions.

2.41.

Several countries of the group of Annex I countries, including the Netherlands, have furthermore committed to rendering financial assistance to the non-Annex I countries, in accordance with the UN Climate Change Conventions.

Kyoto Protocol 1997 and Doha Amendment 2012

2.42.

The Kyoto Protocol was agreed in 1997 in the context of the UN Climate Change Convention. The Netherlands, but also (the predecessor of) the European Union, which then comprised fifteen countries, including the Netherlands, ratified the Kyoto Protocol. It entered into force on 16 February 2005.

2.43.

In the Protocol, the signatories set as their objective for the period 2008-2012 to reduce the mean annual greenhouse gas emissions in developed countries by 5.2% compared to 1990 (Article 3, paragraph 1 of and Appendix B to the Kyoto Protocol). The reduction percentages differ per country. A reduction target of 8% (Appendix B) was set for the European Union for the same period. The EU proceeded to determine the emission reductions per Member State, after consulting the Member States. An emission reduction of 6% was agreed for the Netherlands.

2.44.

Several countries, including the United States and China, did not ratify the Protocol and Canada withdrew from the Protocol in 2011. Before Canada’s withdrawal, the Protocol covered 14% of global emissions.

2.45.

On 8 December 2012, an Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Doha (Qatar). In the Amendment, various countries and the European Union as a whole as well as its individual Member States agreed on a CO2 emission reduction target for the period 2013-2020. The European Union committed to a 20% reduction target as of 2020, compared to 1990. The European Union offered to commit to a 30% reduction target, on the condition that both the developed and the more advanced developing countries commit to similar emission targets. This condition has not materialised thus far nor has the Doha Amendment entered into force yet.

2.46.

Japan, the Russian Federation and New Zealand did not commit to a particular reduction target for this second period. Therefore, the Kyoto Protocol regulates the CO2 emissions of 37 developed countries, namely the (then) 27 individual EU Member States, Australia, Iceland, Croatia, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Norway, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Switzerland and Belarus, as well as the EU as an independent organisation.

Climate change conferences (Conference of the Parties – COP)

2.47.

The UN Climate Change Convention has also provided for the establishment of the Conference of the Parties (COP). All Parties hold a seat on the COP and have one vote. Based on the reports submitted by the Member States, the COP makes annual assessments of the status of the achievement of the Convention’s objective and issues reports about it. The COP can issue decisions during these climate conferences, usually based on consensus.

a) Bali Action Plan 2007

2.48.

The signatories to the UN Climate Change Convention issued various decisions during the climate conference on Bali in 2007, including the Bali Action Plan (Decision 1/CP.13). The preamble to this decision, among others, contains the following sections:

“Responding to the findings of the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and that delay in reducing emissions significantly constrains opportunities to achieve lower stabilization levels and increases the risk of more severe climate change impacts,

Recognizing that deep cuts in global emissions will be required to achieve the ultimate objective of the Convention and emphasizing the urgency1 to address climate change as is indicated in the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

[Note 1: Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Technical Summary, pages 39 and 90, and Chapter 13, page 776.]”

b) The Cancun Agreements 2010

2.49.

At the climate conference in Cancun in 2010, the parties involved issued various decisions, including The Cancun Agreements (Decision 1/CP.16), which contains the following sections, among others:

“Recalling its decision 1/CP.13 (the Bali Action Plan) and decision 1/CP.15 (…),

Noting resolution 10/4 of the United Nations Human Rights Council on human rights and climate change, which recognizes that the adverse effects of climate change have a range of direct and indirect implications for the effective enjoyment of human rights and that the effects of climate change will be felt most acutely by those segments of the population that are already vulnerable owing to geography, gender, age, indigenous or minority status, or disability (…),

4. Further recognizes that deep cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions are required according to science, and as documented in the Fourth Assessment Report of the Inter- governmental Panel on Climate Change, with a view to reducing global greenhouse gas emissions so as to hold the increase in global average temperature below 2°C above pre- industrial levels, and that Parties should take urgent action to meet this long-term goal, consistent with science and on the basis of equity; also recognizes the need to consider, in the context of the first review, as referred to in paragraph 138 below, strengthening the long-term global goal on the basis of the best available scientific knowledge, including in relation to a global average temperature rise of 1.5°C; (…)”

2.50.

At the Cancun climate conference in 2010, the Annex I countries also took the decision which contains the following section, among others:11.

“Decision 1/CMP.6 The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol at its fifteenth session

(…)

Recognizing that Parties included in Annex I (Annex I Parties) should continue to take the lead in combating climate change,

Also recognizing that the contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2007: Mitigation of Climate Change, indicates that achieving the lowest levels assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to date and its corresponding potential damage limitation would require Annex I Parties as a group to reduce emissions in a range of 25–40 per cent below 1990 levels by 2020, through means that may be available to these Parties to reach their emission reduction targets, (…)

4. Urges Annex I Parties to raise the level of ambition of the emission reductions to be achieved by them individually or jointly, with a view to reducing their aggregate level of emissions of greenhouse gases in accordance with the range indicated by Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2007: Mitigation of Climate Change, and taking into account the quantitative implications of the use of land use, land-use change and forestry activities, emissions trading and project-based mechanisms and the carry-over of units from the first to the second commitment period; (…)”

Durban 2011

2.51.

The parties at the climate conference in Durban in 2011 issued several decisions. Decision 1/CP.17 states the following, among other things:

“Recognizing that climate change represents an urgent and potentially irreversible threat to human societies and the planet and thus requires to be urgently addressed by all Parties (…),

Noting with grave concern the significant gap between the aggregate effect of Parties’ mitigation pledges in terms of global annual emissions of greenhouse gases by 2020 and aggregate emission pathways consistent with having a likely chance of holding the increase in global average temperature below 2°C or 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, (…)”

2.52.

At the Durban conference, the Parties also agreed that a new legally binding climate change convention or protocol must be concluded no later than 2015 and must be implemented by 2020. The climate conference which will be held in Paris in December 2015 is a follow-up to this agreement.

In a European context

2.53.

Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) currently reads as follows:

Article 191

1. Union policy on the environment shall contribute to pursuit of the following objectives:

– preserving, protecting and improving the quality of the environment;

– protecting human health;

– prudent and rational utilisation of natural resources;

– promoting measures at international level to deal with regional or worldwide environmental problems, and in particular combating climate change.

2. Union policy on the environment shall aim at a high level of protection taking into account the diversity of situations in the various regions of the Union. It shall be based on the precautionary principle and on the principles that preventive action should be taken, that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source and that the polluter should pay.

In this context, harmonisation measures answering environmental protection requirements shall include, where appropriate, a safeguard clause allowing Member States to take provisional measures, for non-economic environmental reasons, subject to a procedure of inspection by the Union.

3. In preparing its policy on the environment, the Union shall take account of:

– available scientific and technical data,

– environmental conditions in the various regions of the Union,

– the potential benefits and costs of action or lack of action,

– the economic and social development of the Union as a whole and the balanced development of its regions.

4. Within their respective spheres of competence, the Union and the Member States shall cooperate with third countries and with the competent international organisations. The arrangements for Union cooperation may be the subject of agreements between the Union and the third parties concerned.

The previous subparagraph shall be without prejudice to Member States' competence to negotiate in international bodies and to conclude international agreements.

2.54.

Under Article 192 TFEU, the European Parliament and the Council, acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure (meaning on the proposal of the Commission) and after consulting the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) and the Committee of the Regions, generally decide what action is to be taken by the Union in order to achieve the objectives referred to in Article 191 (apart from exception formulated the paragraph 2).

2.55.

Article 193 TFEU currently reads as follows:

Article 193

The protective measures adopted pursuant to Article 192 shall not prevent any Member State from

maintaining or introducing more stringent protective measures. Such measures must be compatible

with the Treaties. They shall be notified to the Commission.

2.56.

Partly as a follow-up to the Kyoto Protocol, the EU formulated its environmental objectives and priorities in Decision no 1600/2002/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down the Sixth Community Environment Action Programme as follows:

“Article 2 Principles and overall aims (…)

2. The Programme aims at:

— emphasising climate change as an outstanding challenge of the next 10 years and beyond and contributing to the long term objective of stabilising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Thus a

long term objective of a maximum global temperature increase of 2 °Celsius over pre-industrial levels and a CO2 concentration below 550 ppm shall guide the Programme. In the longer term this is likely to require a global reduction in emissions of greenhouse gases by 70% as compared to 1990 as identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); (… )”

2.57.

The European Union subsequently converted its objectives in European regulations, including by introducing a large number of directives, among them Directive 2003/87/EC establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community, which introduced the European Union Emission Trading System (ETS). This system only applies to major energy-intensive businesses, such as major electricity generation plants and refineries (hereinafter also referred to as: the ETS businesses). Non-ETS sectors, including transport, agriculture, housing and small companies, do not fall under the scope of the ETS.

2.58.

The preamble to Directive 2009/29/EC amending Directive 2003/87/EC so as to improve and extend the greenhouse gas emission allowance trading scheme of the Community states the following:

“(6) In order to enhance the certainty and predictability of the Community scheme, provisions should be specified to increase the level of contribution of the Community scheme to achieving an overall reduction of more than 20%, in particular in view of the European Council’s objective of a 30% reduction by 2020 which is considered scientifically necessary to avoid dangerous climate change (…).

(13) The Community-wide quantity of allowances should decrease in a linear manner calculated from the mid-point of the period from 2008 to 2012, ensuring that the emissions trading system delivers gradual and predictable reductions of emissions over time. The annual decrease of allowances should be equal to 1.74% of the allowances issued by Member States pursuant to Commission Decisions on Member States’ national allocation plans for the period from 2008 to 2012, so that the Community scheme contributes cost-effectively to achieving the commitment of the Community to an overall reduction in emissions of at least 20% by 2020.

(14) This contribution is equivalent to a reduction of emissions in 2020 in the Community scheme of 21% below reported 2005 levels, (…).”

2.59.

Articles 1 and 9 of the ETS Directive read as follows – following amendment:

Article 1 Subject matter

This Directive establishes a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Community scheme’) in order to promote reductions of greenhouse gas emissions in a cost-effective and economically efficient manner.

This Directive also provides for the reductions of greenhouse gas emissions to be increased so as to contribute to the levels of reductions that are considered scientifically necessary to avoid dangerous climate change.

This Directive also lays down provisions for assessing and implementing a stricter Community reduction commitment exceeding 20%, to be applied upon the approval by the Community of an international agreement on climate change leading to greenhouse gas emission reductions exceeding those required in Article 9, as reflected in the 30% commitment endorsed by the European Council of March 2007.

Article 9 Community-wide quantity of allowances

The Community-wide quantity of allowances issued each year starting in 2013 shall decrease in a linear manner beginning from the mid-point of the period from 2008 to 2012. The quantity shall decrease by a linear factor of 1.74% compared to the average annual total quantity of allowances issued by Member States in accordance with the Commission Decisions on their national allocation plans for the period from 2008 to 2012.

The Commission shall, by 30 June 2010, publish the absolute Community-wide quantity of allowances for 2013, based on the total quantities of allowances issued or to be issued by the Member States in accordance with the Commission Decisions on their national allocation plans for the period from 2008 to 2012.

The Commission shall review the linear factor and submit a proposal, where appropriate, to the European Parliament and to the Council as from 2020, with a view to the adoption of a decision by 2025.”

2.60.

The Communication of the European Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the EESC and the CoR of 10 January 2007, entitled “Limiting Global Climate Change to 2 degrees Celsius. The way ahead for 2020 and beyond”, states the following, among other things:12.

“2. THE CLIMATE CHALLENGE: REACHING THE 2ºC OBJECTIVE

Strong scientific evidence shows that urgent action to tackle climate change is imperative. Recent studies, such as the Stern review, reaffirm the enormous costs of failure to act. These costs are economic, but also social and environmental and will especially fall on the poor, in both developing and developed countries. A failure to act will have serious local and global security implications. Most solutions are readily available, but governments must now adopt policies to implement them. Not only is the economic cost of doing so manageable, tackling climate change also brings considerable benefits in other respects. The EU's objective is to limit global average temperature increase to less than 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels. This will limit the impacts of climate change and the likelihood of massive and irreversible disruptions of the global ecosystem. The Council has noted that this will require atmospheric concentrations of GHG to remain well below 550 ppmv CO2-eq. By stabilising long-term concentrations at around 450 ppmv CO2-eq. there is a 50% chance of doing so. This will require global GHG emissions to peak before 2025 and then fall by up to 50% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. The Council has agreed that developed countries will have to continue to take the lead to reduce their emissions between 15 to 30% by 2020. The European Parliament has proposed an EU CO2 reduction target of 30% for 2020 and 60 to 80% for 2050.”

2.61.

In July 2008, the EESC issued its Opinion on the “Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2003/87/EC so as to improve and extend the greenhouse gas emission allowance trading system of the Community”. This proposal pertains the following, among other things:13.

“6.5 The EESC has therefore paid particular attention to the role of the ETS in delivering equitable and sustainable impact on global GHG reduction. Does it demonstrate that European action is both credible and effective? In this context it has to be stated that the EU target of a 20% reduction in GHG emissions by 2020 compared to 1990 levels (which underlies the ETS and the burden sharing proposals) is lower than the 25-40% reduction range for industrialised nations which was supported by the EU at the Bali Climate Change Conference in December 2007. The Commission starts from the targets as agreed in the European Spring Council 2007 leaving undiscussed whether this level of reduction is really sufficient to achieve global objectives

or whether it is just the maximum reduction that may conceivably be accepted, given the balance of short-term political and economically motivated interests of Member States. The EESC concludes that accumulating evidence on climate change demands the re-setting of targets to achieve greater GHG emission reductions.”

2.62.

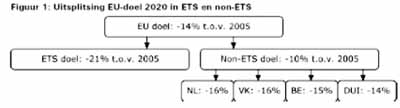

In Decision No 406/2009/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the effort of Member States to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to meet the Community’s greenhouse gas emission reduction commitments up to 2020 (the “Effort Sharing Decision”), the following was considered and adopted to regulate emissions in the non-ETS sectors:

“ (2) The view of the Community, most recently expressed, in particular, by the European Council of March 2007, is that in order to meet this objective, the overall global annual mean surface temperature increase should not exceed 2°C above pre-industrial levels, which implies that global greenhouse gas emissions should be reduced to at least 50% below 1990 levels by 2050. The Community’s greenhouse gas emissions covered by this Decision should continue to decrease beyond 2020 as part of the Community’s efforts to contribute to this global emissions reduction goal. Developed countries, including the EU Member States, should continue to take the lead by committing to collectively reducing their emissions of greenhouse gases in the order of 30% by 2020 compared to 1990. They should do so also with a view to collectively reducing their greenhouse gas emissions by 60 to 80% by 2050 compared to 1990. (…)

(3) Furthermore, in order to meet this objective, the European Council of March 2007 endorsed a Community objective of a 30% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 compared to 1990 as its contribution to a global and comprehensive agreement for the period after 2012, provided that other developed countries commit themselves to comparable emission reductions and economically more advanced developing countries commit themselves to contributing adequately according to their responsibilities and capabilities.

(4) The European Council of March 2007 emphasised that the Community is committed to transforming Europe into a highly energy-efficient and low greenhouse-gas-emitting economy and has decided that, until a global and comprehensive agreement for the period after 2012 is concluded, and without prejudice to its position in international negotiations, the Community makes a firm independent commitment to achieve at least a 20% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 compared to 1990 (…).

(6) Directive 2003/87/EC(1) establishes a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community, which covers certain sectors of the economy. All sectors of the economy should contribute to emission reductions in order to cost-effectively achieve the objective of a 20% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 compared to 1990 levels. Member States should therefore implement additional policies and measures in an effort to further limit the greenhouse gas emissions from sources not covered under Directive 2003/87/EC.

(7) The effort of each Member State should be determined in relation to the level of its 2005 greenhouse gas emissions covered by this Decision, adjusted to exclude the emissions from installations that existed in 2005 but which were brought into the Community scheme in the period from 2006 to 2012. Annual emission allocations for the period from 2013 to 2020 in terms of tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent should be determined on the basis of reviewed and verified data.

(9) To further ensure a fair distribution between the Member States of the efforts to contribute to the implementation of the independent reduction commitment of the Community, no Member State should be required to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 to more than 20% below 2005 levels nor allowed to increase its greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 to more than 20% above 2005 levels. Reductions in greenhouse gas emissions should take place between 2013 and 2020. Each Member State should be allowed to carry forward from the following year a quantity of up to 5% of its annual emission allocation. Where the emissions of a Member State are below that annual emission allocation, a Member State should be allowed to carry over its excess emission reductions to the subsequent years (…).

(17) (17) This Decision should be without prejudice to more stringent national objectives. Where Member States limit the greenhouse gas emissions covered by this Decision beyond their obligations under this Decision in order to meet a more stringent objective, the limitation imposed by this Decision on the use of greenhouse gas emission reduction credits should not apply to the additional emission reductions to attain the national objective. (…)

Article 1 Subject matter

This Decision lays down the minimum contribution of Member States to meeting the greenhouse gas emission reduction commitment of the Community for the period from 2013 to 2020 for greenhouse gas emissions covered by this Decision, and rules on making these contributions and for the evaluation thereof.

This Decision also lays down provisions for assessing and implementing a stricter Community reduction commitment exceeding 20%, to be applied upon the approval by the Community of an international agreement on climate change leading to emissions reductions exceeding those required pursuant to Article 3, as reflected in the 30% reduction commitment as endorsed by the European Council of March 2007 (…).

Article 3 Emission levels for the period from 2013 to 2020.

1. Each Member State shall, by 2020, limit its greenhouse gas emissions at least by the percentage set for that Member State in Annex II to this Decision in relation to its emissions in 2005. (…)

Annex II

Member State greenhouse gas emission limits in 2020 compared to 2005 greenhouse gas emissions levels | |

(…) | |

Netherlands | -16% |

(…)”

2.63.

In the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the regions, entitled “Analysis of options to move beyond 20% greenhouse gas emission reductions and assessing the risk of carbon leakage” of 26 May 2010, the following, among other things, was stated:14.“When the EU decided in 2008 to cut its greenhouse gas emissions, it showed its commitment to tackling the climate change threat and to lead the world in demonstrating how this could be done. The agreed cut of 20% from 1990 levels by 2020, together with a 20% renewables target, was a crucial step for the EU's sustainable development and a clear signal to the rest of the world that the EU was ready to take the action required. The EU will meet its Kyoto Protocol target and has a strong track record in climate action.

But it has always been clear that action by the EU alone will not be enough to combat climate change and also that a 20% cut by the EU is not the end of the story. EU action alone is not enough to deliver the goal of keeping global temperature increase below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels. All countries will need to make an additional effort, including cuts of 80- 95% by 2050 by developed countries. An EU target of 20% by 2020 is just a first step to put emissions onto this path.

That was why the EU matched its 20% unilateral commitment with a commitment to move to 30%, as part of a genuine global effort. This remains EU policy today.

Since the EU policy was agreed, circumstances have been changing rapidly. We have seen an economic crisis of unprecedented scale. It has put huge pressure onto businesses and communities across Europe, as well as causing huge stress on public finances. But at the same time, it has confirmed that there are huge opportunities for Europe in building a resource-efficient society.

We have also had the Copenhagen summit. Despite the disappointment of failing to achieve the goal of a full, binding international agreement to tackle climate change, the most positive result was that countries accounting for some 80% of emissions today made pledges to cut emissions, even though these will be insufficient to meet the 2°C target. It will remain essential to integrate the Copenhagen Accord in on-going UNFCCC negotiations (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). But the need for action remains as valid as ever.

The purpose of this Communication is not to decide now to move to a 30% target: the conditions set are clearly not met. To facilitate a more informed debate on the implications of the different levels of ambition, this Communication sets out the result of analysis into the implications of the 20% and 30% targets as seen from today's perspective. (…)”

2.64.

In the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the regions of 8 March 2011, entitled “A roadmap for moving to a competitive low carbon economy in 2050”, the following was stated, among other things:15.

“ 1. EUROPE'S KEY CHALLENGES

(…) In order to keep climate change below 2ºC, the European Council reconfirmed in February 2011 the EU objective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80-95% by 2050 compared to 1990, in the context of necessary reductions according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change by developed countries as a group. This is in line with the position endorsed by world leaders in the Copenhagen and the Cancun Agreements. These agreements include the commitment to deliver long-term low carbon development strategies. Some Member States have already made steps in this direction, or are in the process of doing so, including setting emission reduction objectives for 2050. (…)

2. MILESTONES TO 2050

The transition towards a competitive low carbon economy means that the EU should prepare for reductions in its domestic emissions by 80% by 2050 compared to 1990. The Commission has carried out an extensive modelling analysis with several possible scenarios showing how this could be done, (…).

This analysis of different scenarios shows that domestic emission reductions of the order of 40% and 60% below 1990 levels would be the cost-effective pathway by 2030 and 2040, respectively. In this context, it also shows reductions of 25% in 2020. (…). Such a pathway would result in annual reductions compared to 1990 of roughly 1% in the first decade until 2020, 1.5% in the second decade from 2020 until 2030, and 2% in the last two decades until 2050. The effort would become greater over time as a wider set of cost-effective technologies becomes available. (…)

Emissions, including international aviation, were estimated to be 16% below 1990 levels in 2009. With full implementation of current policies, the EU is on track to achieve a 20% domestic reduction in 2020 below 1990 levels, and 30% in 2030. However, with current policies, only half of the 20% energy efficiency target would be met by 2020.

If the EU delivers on its current policies, including its commitment to reach 20% renewables, and achieve 20% energy efficiency by 2020, this would enable the EU to outperform the current 20% emission reduction target and achieve a 25% reduction by 2020. This would require the full implementation of the Energy Efficiency Plan (…)

6. CONCLUSIONS

(…) In order to be in line with the 80 to 95% overall GHG reduction objective by 2050, the Roadmap indicates that a cost effective and gradual transition would require a 40% domestic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990 as a milestone for 2030, and 80% for 2050. (…)

(…) This Communication does not suggest to set new 2020 targets, nor does it affect the EU's offer in the international negotiations to take on a 30% reduction target for 2020, if the conditions are right. This discussion continues based on the Commission Communication from 26 May 2010.”

2.65.

On 15 March 2012, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the Roadmap referred to in 2.64, in which the Roadmap as well as the path and specific milestones for the reduction of the Community’s domestic emissions of 40%, 60% and 80% for 2030, 2040 and 2050, respectively, were endorsed.16.

2.66.